Does an Honor Code Make It Too Easy to Cheat

"Cheating is so normalized": How students regard and disregard the Honor Code

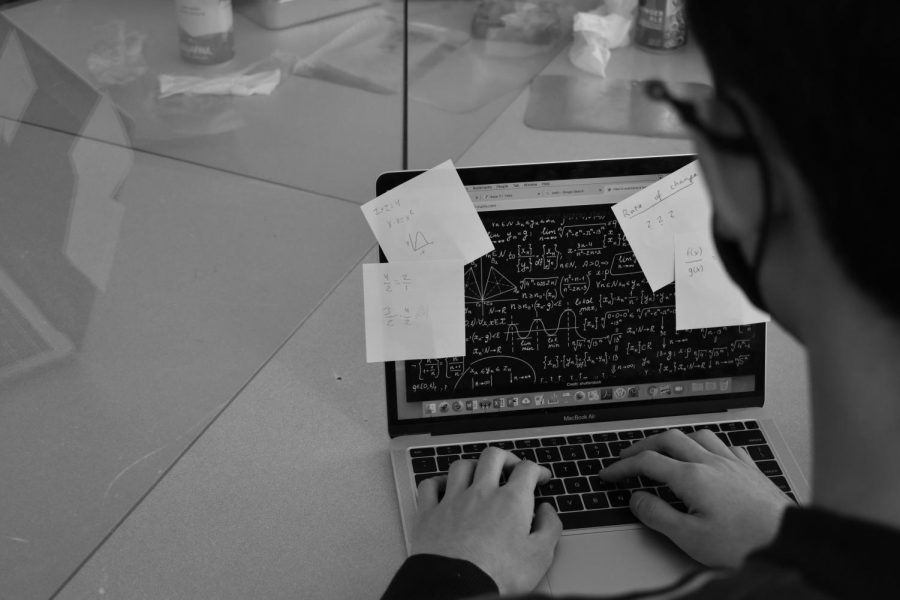

The 54th page of the Family Handbook begins: "As a student at the Horace Mann School, I will not lie, cheat, plagiarize, or steal." The page is titled "The Honor Code," and students are required to sign the document and abide by each of its nine policies — if they do not, they will be subject to a set of standard punitive procedures. The document defines the "honor" of students at the school: students will work individually when it is asked of them, provide assistance only when it is allowed, oppose any instances of academic dishonesty, and "respect the trust placed in [them] by the school administration and faculty and [their] peers." A 2015 study by Dr. Donald McCabe and the International Center for Academic Integrity conducted with over 70,000 students at more than 24 high schools in the United States states that 64 percent of students admitted to cheating on a test, 58 percent admitted to plagiarism and 95 percent said they participated in some form of cheating, whether it was on a test, plagiarism, or copying homework. According to an anonymous Record poll conducted this week to which 144 Upper Division students responded, 80.6% of students believe that the Honor Code is valuable. Yet, 68.1% of students have broken the Honor Code in at least one way. There is an idea that the code is a contractual agreement and once a student has signed it, they are agreeing to abide by whatever the document states, Dean of Students Michael Dalo said. However, signing the Honor Code is not actually legally binding, math teacher Charles Worrall said. Rather, it is a moment to acknowledge the values that it represents. Although Mateo* (12), who is anonymous so as not to get in trouble for admitting to breaking the Honor Code, signs the Honor Code in advisory at the beginning of each school year, he does not see it as a valid document. Students are not given a choice when signing this contract, and this forced nature causes the document to have little significance, he said. While Mateo doesn't like the idea of cheating because it could detrimentally impact his peers, he does not feel a commitment to the honor of the school. "I don't feel at all like I owe it to Horace Mann to follow the words that are on the paper that they make us sign at the beginning of the year." Whether students sign the Honor Code or not, math teacher Chris Jones finds value in the conversations the code sparks in advisory. "That process where we're having that discussion [about cheating], regardless of whether it stops cheating or not, is educating people on what it means to be an honest scholar." "In an ideal situation, we wouldn't need to sign the Honor Code because there would be this sense of value and this importance of moral character that eliminates the need to do that signature," Dalo said. For now, however, the student body's signatures remain an integral part of their commitment to academic honesty at this institution. Still, signing the Honor Code does not necessarily prevent students from cheating. CHEATING IN CLASSES Bianca* (11), who is anonymous so as not to be penalized for past cheating, said that cheating in a math class at school is not how it is depicted in movies — it is not necessarily as explicit as peeking over to copy from your neighbor's paper. "I've heard of some people putting their calculator on the floor and using it during a test, but I think most people just [cheat] on the take-homes because the other stuff isn't worth the headache," said Georgia* (12), who is anonymous because she is admitting to violating the Honor Code. Cheating on math assessments usually happens when students check over answers on take-home assessments that are supposed to reflect their individual work, Bianca said. While she understands that this is cheating, she too participates. Ultimately, Bianca said that in order to get the grade she wishes to receive, she has to utilize all that is available to her — including her peers' work. Bianca is one of the 32.6% of students polled who participates in this form of dishonesty. Bianca feels pressure to cheat because she knows that students around her will do so. If she does not use the resources available to her, including those of dishonest nature, she feels she will be at a disadvantage in the classroom setting. Gertrude* (11), who is anonymous because she is sharing personal information about cheating, also cheats in order to improve her grades. She feels that the grades she receives don't always reflect the work that she puts into assignments. "I know that I'm hard-working, and I feel like my grades should reflect that," she said. "So if there's something that I can do to make it closer to that, then I will do it without actually feeling guilty because I feel like there is a level of deserving it too, which almost tends to justify it." It is a discouraging situation for many students when they feel as if they are falling behind in a class. Collaboration on individual assessments can alleviate some of this feeling, said Saul* '20, who is anonymous because he did not report past instances of cheating. "A lot of people would have otherwise stopped taking courses and high-level courses if they didn't have that opportunity to collaborate with other people." On the other hand, Abigail Morse (12) sees no possible justification for academic dishonesty. Even though she sometimes struggles with take-home assignments, she chooses never to collaborate with her classmates, knowing that her morality should be at the forefront of her academic career. "It does feel very isolating when you can't talk to anyone and you're struggling on something, even though you are putting in hours upon hours of work. But [cheating] really just harms everyone else, because if someone doesn't want to cheat then they're at a disadvantage. Although Dalo understands the frustration of working hard and not receiving the results one believes that they deserve, he does not believe that this is a justification for cheating. "If a student is in that place of frustration, cheating is not the answer," he said. "The answer is engaging with the teacher to talk about what more can be done to help and support the student to get the grades to where they want them to be." Gertrude believes that looking up answers to an assessment can be harmful to a productive academic environment, but she thinks it is sometimes justified if she understood the problem in class but could not apply it to her work at home. "If I understand what the Internet is telling me, then I feel like in a way I've gone through that intellectual process myself, just with some help," she said. Comprehension of a topic or problem, whether it comes from class, the Internet, or a friend, is beneficial to any student's education, Saul said. "If there's a very hard problem on a physics problem set, and your friend wouldn't have otherwise gotten it, they're better off working with you towards understanding that solution." Mateo thinks that collaboration on assignments can be especially helpful in math class. On take-home assessments, students might come across a problem they do not know how to solve, and when they are going through their notes, that student might not understand the solution that they learned in class. In these circumstances, Mateo does not see why problem-solving with the people the student learned the material with would be an issue. "If you asked most people who collaborated on take-homes, I don't think that they would feel like it was because they just had the opportunity, it's also because it actually helped them learn the math." Similarly, although using SparkNotes is usually deemed a form of cheating, it can sometimes be a helpful resource for students trying to get a grasp on difficult material or those written in a complex style, such as works by Shakespeare, Head of English Department Vernon Wilson said. At the same time, it is never permissible to read explanations online instead of the actual text, he said. 36.1% of students who responded to the poll have used SparkNotes instead of doing reading when they were told not to. When he first began teaching at the school, English teacher Andrew Fippinger used to tell his students that reading any outside source about the provided texts was considered cheating. Over time, however, he realized that his message, no matter how passionately explained, was not being understood. Fippinger now chooses to accept the fact that some of his students will be supplementing, or even replacing, their readings with an online study guide like SparkNotes or Shmoop. No matter how common, this form of academic dishonesty is highly discouraged by all members of the English Department, he said. However, students can benefit from online analyses, Saul said. "If I derive an understanding of the text from talking to my friend versus doing it on SparkNotes, that doesn't seem very different to me." To read outside sources is to diminish the value of the English classroom environment, Fippinger said. "The point of English is reading stuff together: it's complicated, it's difficult, it's frustrating, and sometimes it takes a long time," he said. "But we're working together to try to figure out what it means, to try to interpret it. If you're letting someone else do that for you, it's like having somebody do your math homework for you — you don't learn anything." However, collaboration on individual assessments is prevalent in math classes, especially on take-home assignments. "I don't think I've ever seen a take-home that people didn't collaborate on, and I don't think I've ever done a take-home math test without collaborating," Mateo said. Before his students submit take-home assignments, math teacher Charles Worrall asks them to sign a document stating that they have neither given nor received help on the exam. Worrall understands that signing the paper is in no way a legal document; rather, it is a symbolic act that the students must complete. "It's a sort of participation in a cultural moment," he said. He sees it as a promise that the students have "bought into" the importance of doing their own work. Sometimes, students also get help from those older than them. "Occasionally, they get help from their parents or from an adult outside the community, which is extraordinarily fraught because we want parents to be partners in thinking of the school as really educating kids," Worrall said. Jolene* (12), who is anonymous because she did not report past instances of cheating, remembers students in two different math classes taught by the same teacher communicating about their exams — the students from the morning class would tell the students in the afternoon class what to expect. This actually caused the later class to have a significantly higher testing average than the other, she said. "I took a few classes where some students would call each other and trade answers on the take-home tests, go over their answers with each other and even divide up problems," said Scott* (12), who is using anonymity to report instances of cheating he has witnessed. Scott and his friends did not cheat on these take-home tests. He was initially unaware that this type of cheating was even happening, and he did poorly on the assessments. "I put my best effort into it, and the people who cheated and didn't understand the work that they submitted did much better," he said. Worrall understands that he cannot prevent all forms of dishonesty — nor would he want to have that kind of control. "I want to make it hard enough to cheat that it takes work," he said. "If we could totally shut down all the opportunities of cheating, I think this would actually be a lesser school because kids wouldn't learn to make these decisions," he said. In order for students to really benefit from his class, Worrall wants them to make the active choice not to cheat on the assignments. It is more important for students to learn morals than it is to learn academics, World Languages Department Chair Maria del Pilar Valencia said. "The most important thing is that in order to function properly as a society, as an intellectual society, as an academic society, we have to be honest, responsible citizens," she said. "The [learning of] language comes afterwards." Academic dishonesty in a language classroom comes in the same forms as many other departments — students share individual work and copy each other's answers — but the language department must deal with an added layer: students' use of online translators. "When you translate a document before reading it, it is not your work because you're not showing your ability to understand, you're showing Google's ability to translate," Valencia said. According to the poll, 41% of students have used an online translator when they were forbidden from doing so. Google Translate can be a helpful tool for smaller assignments, said Abraham* (10), who is anonymous because he has not reported instances of academic dishonesty that he has witnessed in the past. "Sometimes the directions for the homework can be long or it just looks annoying to read, so people just copy and paste it into Google Translate to make it easier." This dishonesty is particularly fraught because it interferes with the student's progress in the classroom setting, Valencia said. If a student is cheating, their teacher is unaware of their actual progress. "We need to see where you are in order to help you make progress," Valencia said. "Kids are betraying their teachers, but mostly themselves [by cheating]. We cannot help them learn the language if we don't know how they are really doing." Worrall hopes the repercussions for cheating — both academic and moral — are enough to dissuade students from cheating, he said. "I want kids to have to think about those decisions and the consequences of them — which often are not just getting in trouble," he said. "It's about thinking about what they've done after the fact and realizing that they delegitimize some intellectual achievement that they could have had." Similarly, math teacher Dr. Linda Hubschman hopes her students recognize the gap in education that is created when a student cheats. "An assessment is supposed to be an opportunity for students to both learn for themselves and to share with me their understanding of a topic," she said. "Using outside resources prevents this, thereby stifling the learning process." Students may feel pressure to cheat, but they must ultimately keep their morality at the forefront of their decision-making process, Valencia said. "Kids feel that pressure of getting good grades, but the good grades have to come out of learning." Worrall is aware of the possibilities of academic dishonesty within his classroom, and he attempts to mitigate these occurrences through the work he assigns. "I try to make my take-home assignments have an open-note and open-book quality because I don't like the idea of putting kids into situations where it's really easy to cheat," he said. If students are given ample opportunity to cheat on a test, they will feel pressure to do so, knowing that their classmates may do so as well, he said. "Cheating is so normalized that I don't think people think about it for even a second," Georgia said. There is a certain entitlement that students at the school feel because they know they can get away with it, she said. To minimize cheating in her classes, Valencia is clear about how she would like assignments to be completed. "I always let my kids know that homework is open book, and I give specific rules when it comes to group work," she said. Valencia does this to ensure that her students know what is expected of them — and they are never expected to use an online translator. Dean of the Class of 2023 Chidi Asoluka attempts to create an environment in his classes that pushes students not to feel the need to cheat, he said. He asks broad, thought-provoking questions that students won't cheat on — not only because they won't be able to find the answers online, but because they will actually be interested in what they can come up with. "Teachers sometimes create an environment where it feels like responses [written on SparkNotes] are the ones we are looking for," Asoluka said. To combat this, Asoluka is informal in his own responses, reminding students that what is correct is not always what he is looking for. Rather, he wants students to be genuine in their work. He asks himself: "What can I do as a teacher to help you see that I actually don't really value that kind of voice, I value your voice? My hope is that if I can do that enough in the classroom, then the essays will be their voice, and there isn't a desire to take on the voice of someone else." Fippinger, too, wants to make clear what he expects of his students. For this reason, he sees value in asking his advisees to sign the Honor Code every September, he said. "I do think it has real value in sort of forcing you at least once a year to think about these things, to remind you that these are things that go against the values of the school, to remind you that we care enough to remind you and to put it in writing and have you sign it," Fippinger said. "I'm always sort of glad as a teacher when that moment comes around, even though my advisees usually try to make it into a joke." Fippinger can often tell when students are reading online sources before class discussions. When a student raises a discussion point in class that has a formulaic quality or an overly completed analysis, he guesses that the student's perspective is not actually their own, he said. If this occurs multiple times, Fippinger approaches the student outside of class. During this meeting, he mentions that their answers seem similar to an online study guide and says that he is more interested in hearing the questions the student might have or their authentic responses to other students' thoughts, he said. On the other hand, English teacher Stan Lau notices patterns in his students' work. If a student uses vocabulary or terms that do not match their past assignments or articulates a "graduate-level" argument while struggling to understand the basic plot of the reading material, he begins to wonder why this might be the case. In these situations, Lau connects with the student and asks them to walk him through their thought process or explain the context in which they used the word, always with the presumption of good intentions. It is nearly impossible to catch all instances of cheating, Fippinger said. "I wouldn't be surprised if you told me right now there are lots of students who read SparkNotes, repackage it subtly, and I have no idea." Sometimes, Fippinger gives surprise quizzes to see who in the class is actually reading the material, he said. Designing these quizzes is often difficult. There has to be a balance between making the questions specific enough for students who only read online summaries, but easy enough for students who actually did the reading. Teachers often use the Honor Code as a platform to speak about how they catch instances of cheating, Morse said. "They know a lot more than students do about how to tell when someone is not doing their own work." Besides using online study guides, the most common — and most strictly punished — form of academic dishonesty that English teachers face is plagiarism, Wilson said. However, only 3.5% of polled students said that they had at some point plagiarized writing. "Plagiarism is often very ambiguous," Fippinger said. "[The Honor Code] makes it clear you are not allowed to do these things. If you do them, you are making the decision — even if you didn't quite mean to make the decision — you're making a decision to violate the honor code." However, Fippinger does not believe students who plagiarize on essays do so maliciously. "They are not lying cheaters who are trying to prove to the world that they can get away with cheating." If a student makes a conscious decision to plagiarize on an essay, they are almost always under a number of pressures that led to this decision, he said. Sometimes, students violate the school's policies unintentionally, specifically in the realm of plagiarism, Dean of the Class of 2024 Stephanie Feigin said. One of these instances occurs when students visit websites to gain inspiration for their work and accidentally put in those exact ideas — or even the exact phrasing — that they read. "Students might think they just want to understand the plot of a scene, for example, but then their eyes start to wander further down the webpage, and then they get to analysis and that's when the temptation to keep reading because you think it's interesting [begins]," Lau said. "Before you know it, either consciously or subconsciously that analysis that you didn't actually come up with comes through in a class discussion or on a paper." Unfortunately, because that student still submitted work that was not theirs, the consequences remain, Fippinger said. When Fippinger realizes that one of his students has plagiarized, he sits down with the student to talk about their mistake before he brings the issue to the administration. "It's often a pretty emotional conversation, actually," he said. "Students who I've had plagiarize often feel a real sense of shame. Sometimes they are angry with me, sometimes they are angry with themselves, but ideally it can ultimately become — in addition to whatever disciplinary stuff happens in the administrative office — a moment between me and the student to work through what happened and move forward in a way that's actually helpful." Students are not predisposed to cheating, Alex Rosenblatt (11) said. Instead, cheating occurs on a case-by-case basis and is caused by external pressures. Students are attempting to maintain good grades while balancing familial and social worries, so cheating sometimes seems like the best way to fulfill those needs, they said. "A lot of [students] have a sense of almost panic at the thought of anything happening that jeopardizes this future that they think they are supposed to fulfill," Worrall said. "For me as a teacher, I think that the Honor Code is a tool in pushing back against the lies that are actually at the foundation of that sense of panic, and that sense of necessity of fulfilling certain criteria in your life or else you are a failure." This pressure increased dramatically for high school students from when they were in middle school, Abraham said. "People are a lot more worried about their grades in high school, and they'll be a lot more upset about a B+ than they would in middle school," Abraham said. "I definitely didn't think that my grades were as important to my life as I do now, just because they're not taken into consideration for college applications." If a student feels that they have been consistently putting in their best work, and they are not receiving the results that they want, they then may turn to the internet for help, Fippinger said. He can imagine some students believing that a website presents better work than that which they could create. "It is important for me to teach kids more than just math," Worrall said. "I am trying to teach them, in some sense, about good living. Part of teaching kids that is about putting them into situations where they have to make ethical choices." HISTORY The Honor Code may not be followed perfectly, but the document is still an essential part of the school's values, Dalo said. The document puts the school's beliefs surrounding academic integrity into words and onto a piece of paper. It has been twenty years since the original Honor Code was passed, but it is still the school's moral and ethical code when it comes to dishonesty in the classroom, he said. In the fall of 2000, Daniel Seltzer '01, a representative on the Governing Council (GC) — a body of the student government composed of faculty and students who met to vote on bills that pertained to issues at the school — pitched a bill titled the "Academic Honor Code Resolution." The bill called for the administration to enact an academic honor code that would forbid all types of cheating and to create a set of punishments for violations of said code. After Seltzer's original proposal, the GC asked him to draft a physical code. Seltzer created the document by looking at the academic codes of various preparatory schools and universities, he said. He constructed a short, comprehensive list of what he hoped students would abide by in order to create a fairer learning environment. The bill detailed the various ways in which students cheated — plagiarism, sharing answers to a test, and writing hints for or answers to an exam on body parts — and it stated that cheating had become a "black eye" on the student body at Horace Mann. To amend this situation, the bill suggested that the administration must play a large role in demonstrating the unacceptability of a student advancing themselves by dishonorable means. After three weeks of intense discussion among the members of the GC, the bill was passed by an overwhelming majority of 25 to 6, according to a Record article (Volume 98, Issue 9) from that week. The final resolution from Seltzer was a half-page Honor Code written in accordance with the school's Family Handbook section on cheating, including a statement that stated that cheating of any form was a direct trespass of the code. However, on top of fervent debates about the "ambiguous" nature of the wording of the code, the GC's decision sparked a wave of adamant student op-eds both for and against the new bill. In an article titled "State of the GC: Chair Finn ponders honor code" (Volume 98, Issue 14) commending the GC for their decision to pass the Honor Code, then senior and Chair of the GC Meridith Finn '01 acknowledged that this new rule might incite a wave of student disagreement. "There are going to be critics of the Honor Code whether it is long or short, detailed or vague, and a happy medium needs to be met," she wrote. Her expectations rang true in the months following the GC's passing of the bill. About a month after the GC passed the Honor Code and it was signed by former Head of School Lawrence Weiss, Weiss presented the specifics of the code to the Upper Division at an assembly. According to a Record article (Volume 98, Issue 14) about the assembly, Weiss said of the Honor Code, "This is serious, but it's also very positive for this community. If we can take major steps forward in this area, we will have dealt with a problem that has existed at this school in a comprehensive manner that included students, faculty, administrators, and parents." However, after Weiss' presentation, several op-eds were published in the Record by dissenting students and alumni. In a letter to the editor (Volume 98, Issue 16) titled "Code is just rhetoric for now, says HM Alumni," Donald S. Hillman '42 acknowledged the potential upsides to the Honor Code but remarked that without effective enforcement it would be useless. "In its present state of limbo, the Code is pure window dressing and nothing more," Hillman wrote. Some dismissed the code in its entirety. Fleming published a piece titled "We don't need code to be honorable" (Volume 98, Issue 18) about why the Honor Code would not be successful. "If cheating and plagiarism are indeed a problem at Horace Mann, we need something less cosmetic than wasting a lot of paper and more effective than patting ourselves on the back because every single student's signature is now on file somewhere," she wrote. In that same issue, Mike Pareles '03 attacked the mandatory aspect of the Code, arguing that cheating would simply become "more sneaky and insidious" than before. "Instead of protecting the high moral and academic standards to which Horace Mann has always held itself, the Honor Code puts students at unnecessary risk," he wrote. "This is self-evident when you consider that by its very own mandatory nature, it nullifies whatever effect it may have had." This initial disconnect between students and teachers regarding the honor code still holds true today. Students and teachers continue to have conflicting opinions about the morality of cheating and its applications in regards to the Honor Code. Seltzer did not realize the impact his creation would have, he said. The creation and establishment of the Code occurred so quickly that he could not have imagined what it would become, he said. "I am actually really surprised to hear that it has become a punitive, impactful thing." Although the Honor Code had a larger impact than its authors originally envisioned, the document's values are not upheld completely. The code is a piece of the school's culture, but no one claims that it maintains the values it presents all by itself, Dean of the Class of 2022 Glenn Wallach said. REPERCUSSIONS When a student commits a first offense against the Honor Code on a graded assignment, the student receives a "double F" on the assignment. This means that the student has two 'F' grades averaged into their final grade. If a student is thinking about cheating because they are under some sort of academic pressure, they should remember the official consequences of their actions, Feigin said. "A late penalty is a much better consequence than a double F on an assignment." Morse does not cheat because she understands that there are always other options, she said. "You can always tell a teacher if you are having a rough day. You don't need to cheat to get a better grade." She believes that the punitive section of the Honor Code does deter students from cheating — "this punishment, especially for Horace Mann students, has got to be very worrying," she said. Dalo noted that most incidents of academic dishonesty that reach his office have to do with graded assignments. On ungraded, smaller homework assessments, teachers handle cheating in their own ways and often in consultation with grade deans. Dean of the Class of 2022 Dr. Glenn Wallach has encountered occasional incidents of academic dishonesty in his 16 years at the school; however, it is rare that a student commits academic dishonesty a second time, he said. Wallach credits this lack of repetition to the educational element of the consequences students receive for democracy that is currently in place. After a formal repercussion is given, a dean meets with the student who cheated to speak about a plan for the future, Feigin said. During this meeting, Feigin tries to find out what kind of pressures the student was under and the ways in which those stressors can be ameliorated so as to make sure the incident is not repeated. "The attempt is to let them know that we're on their side — that this is not going to be a moment that defines them," she said. In his conversations with students who have cheated, Asoluka tries to ensure that these actions won't be repeated, he said. Although it is his role to penalize the students for their wrongdoing, it is always his goal to help them do better in the future. "My role before anything else is always as an educator," he said. "I don't consider myself a hardcore disciplinarian. I'm an educator, and an educator always leads with love and I think that's what I try to do." Although teachers do their best to ameliorate conditions that lead to cheating, students have, in extremely rare cases, committed a second offense of academic dishonesty. According to the family handbook, this situation is taken more seriously than the original violation. In addition to receiving the same "double F," the student will be suspended in almost all cases. If the incident is serious enough, the student may be expelled. "When a kid is expelled here, I believe it's not to rid our school of some 'bad seed,'" Worrall said. "Instead, it's just that this student needs a lesson." The penalty system at the school is designed to be educational rather than punitive. "I think that the Honor Code is actually a teaching tool, not a method of punishing kids for wrongdoing," Worrall said. At the same time, these consequences are necessary to establish the expectations of the school, Valencia said. The school must communicate that taking any kind of shortcuts is unacceptable. "We need to make clear that work that is not yours cannot be credited as yours," she said. "We need to communicate that that is not the way that we build a community." Students cheat for many reasons, but the formal consequences of cheating are the same no matter the occurrence, Feigin said. There is no way to truly know what went through a student's mind at the moment of the infraction, so the school does not feel capable to determine the severity of the consequences they give. Rather than modifying each repercussion, deans alter the conversations they have with students based on the type of incident, she said. "We're going to address [unintentional cheating] differently than the student who intentionally did it because that student who intentionally did it needs a different set of guiding tools." The consequences for students in various grades do sometimes differ, Dalo said. Because ninth graders are still learning how and when to put citations on their work, consequences for younger students can be more lenient. However, Feigin understands the emotional impact that these incidents have on students, and she tries to help the students move on as soon as the consequences have been given. "Every student I've ever met with feels badly about what happened and didn't mean to disappoint and said had they had another moment [they] would have done things differently," she said. "When they walk out the door, we get to move past it. My goal is not to have a conversation with them about the incident every time they walk through the door."

Source: https://record.horacemann.org/6119/features/cheating-is-so-normalized-how-students-regard-and-disregard-the-honor-code/

0 Response to "Does an Honor Code Make It Too Easy to Cheat"

Post a Comment