What Era Was Religious Art and Statuary Destroyed in History

Catholic fine art is art produced by or for members of the Catholic Church. This includes visual art (iconography), sculpture, decorative arts, applied arts, and compages. In a broader sense, Catholic music and other art may be included as well. Expressions of art may or may not attempt to illustrate, supplement and portray in tangible form Catholic teaching. Catholic fine art has played a leading role in the history and development of Western art since at least the 4th century. The primary subject matter of Catholic art has been the life and times of Jesus Christ, along with people associated with him, including his disciples, the saints, and motifs from the Catholic Bible.

The earliest surviving artworks are the painted frescoes on the walls of the catacombs and meeting houses of the persecuted Christians of the Roman Empire. The Church in Rome was influenced by the Roman art and the religious artists of the time. The rock sarcophagi of Roman Christians exhibit the earliest surviving carved statuary of Jesus, Mary and other biblical figures. The legalisation of Christianity with the Edict of Milan (313) transformed Cosmic art, which adopted richer forms such as mosaics and illuminated manuscripts. The iconoclasm controversy briefly divided the Western Church and the Eastern Church, after which artistic development progressed in split directions. Romanesque and Gothic art flowered in the Western Church as the way of painting and statuary moved in an increasingly naturalistic direction.

The Protestant Reformation in the 16th century produced new waves of paradigm-devastation, to which the Catholic Church building responded with the dramatic, elaborate emotive Bizarre and Rococo styles to emphasise beauty as a transcendental. In the 19th century the leadership in Western art moved away from the Catholic Church which, after embracing historical revivalism, was increasingly affected by the modernist movement, a movement that in its "rebellion" against nature counters the church building's emphasis on nature as a good creation of God.

Ancestry [edit]

Christian art is nearly every bit quondam as Christianity itself. The oldest Christian sculptures are from Roman sarcophagi, dating to the outset of the 2nd century. As a persecuted sect, however, the earliest Christian images were arcane and meant to be intelligible but to the initiated. Early on Christian symbols include the dove, the fish, the lamb, the cross, symbolic representation of the Four Evangelists as beasts, and the Skillful Shepherd. Early Christians too adapted Roman decorative motifs like the peacock, grapevines, and the good shepherd. Information technology is in the Catacombs of Rome that recognizable representations of Christian figures first appear in number. The recently excavated Dura-Europos house church building on the borders of Syrian arab republic dates from around 265 Advertisement and holds many images from the persecution period. The surviving frescoes of the baptistry room are among the most aboriginal Christian paintings. We can see the "Good Shepherd", the "Healing of the paralytic" and "Christ and Peter walking on the water". A much larger fresco depicts the ii Marys visiting Christ'south tomb.[2]

Virgin and Child. Wall painting from the early on catacombs, Rome, 4th century.

In the 4th century, the Edict of Milan immune public Christian worship and led to the development of a monumental Christian art. Christians were able to build edifices for worship larger and more handsome than the furtive meeting places they had been using. Existing architectural formulas for temples were unsuitable because pagan sacrifices occurred outdoors in the sight of the gods, with the temple, housing the cult figures and the treasury, as a properties. Equally an architectural model for large churches, Christians chose the basilica, the Roman public building used for justice and administration. These basilica-churches had a eye nave with one or more aisles at each side and a rounded apse at i terminate: on this raised platform sabbatum the bishop and priests, and besides the altar. Although information technology appears that early altars were constructed of wood (every bit is the instance in the Dura-Europos church) altars of this menstruation were built of stone, and began to become more than richly designed. Richer materials could now be used for art, such as the mosaics that decorate Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome and the 5th century basilicas of Ravenna, where narrative sequences begin to develop.

Much Christian art borrowed from Regal imagery, including Christ in Majesty, and the employ of the halo as a symbol of sanctity. Tardily Antique Christian art replaced classical Hellenistic naturalism with a more abstract aesthetic. The primary purpose of this new manner was to convey religious pregnant rather than accurately render objects and people. Realistic perspective, proportions, light and colour were ignored in favor of geometric simplification, opposite perspective and standardized conventions to portray individuals and events. Icons of Christ, Mary and the saints, ivory carving,[3] and illuminated manuscripts became important media – even more than important in terms of modern understanding, as nearly all of the few surviving works, other than buildings, from the period consist of these portable objects.

Byzantine and Eastern art [edit]

The dedication of Constantinople every bit capital in 330 AD created a bang-up new Christian creative center for the Eastern Roman Empire, which soon became a separate political unit. Major Constantinopolitan churches built under the Emperor Constantine and his son, Constantius Two, included the original foundations of Hagia Sophia and the Church of the Holy Apostles.[4] As the Western Roman Empire disintegrated and was taken over by "barbarian" peoples, the art of the Byzantine Empire reached levels of sophistication, power and artistry non previously seen in Christian art, and prepare the standards for those parts of the West still in touch with Constantinople.

This achievement was checked past the controversy over the apply of graven images and the proper interpretation of the 2d Commandment, which led to the crisis of iconoclasm or destruction of religious images, which rocked the Empire between 726 and 843. The restoration of orthodox iconodulism resulted in a strict standardization of religious imagery inside the Eastern Orthodox Church. Byzantine art became increasingly bourgeois, as the form of images themselves, many accorded divine origin or thought to have been painted by Saint Luke or other figures, was held to have a status not far off that of a scriptural text. They could be copied, just non improved upon. As a concession to Iconoclast sentiment, monumental religious sculpture was effectively banned. Neither of these attitudes were held in Western Europe, but Byzantine fine art yet had great influence in that location until the High Middle Ages, and remained very popular long after that, with vast numbers of icons of the Cretan School exported to Europe as tardily every bit the Renaissance. Where possible, Byzantine artists were borrowed for projects such every bit mosaics in Venice and Palermo. The enigmatic frescoes at Castelseprio may be an case of work past a Greek artist working in Italy.

The art of Eastern Catholicism has always been rather closer to the Orthodox art of Greece and Russia and in countries near the Orthodox world, notably Poland, Catholic fine art has many Orthodox influences. The Blackness Madonna of Częstochowa may well take been of Byzantine origin – information technology has been repainted and this is hard to tell. Other images that are certainly of Greek origin, like the Salus Populi Romani and Our Lady of Perpetual Help, both icons in Rome, accept been subjects of specific veneration for centuries.

Although the influence has often been resisted, especially in Russian federation, Cosmic fine art has also afflicted Orthodox depictions in many respects, especially in countries similar Romania, and in the post-Byzantine Cretan School, which led Greek Orthodox fine art nether Venetian dominion in the 15th and 16th centuries. El Greco left Crete when relatively young, but Michael Damaskinos returned after a brief menstruum in Venice, and was able to switch between Italian and Greek styles. Even the traditionalist Theophanes the Cretan, working mainly on Mount Athos, nonetheless shows unmistakable Western influence.

Catholic doctrine on sacred images [edit]

The Cosmic theological position on sacred images has remained finer identical to that set out in the Libri Carolini, although this, the fullest medieval expression of Western views on images, was in fact unknown during the Center Ages. Information technology was prepared circa 790 for Charlemagne afterward a bad translation had led his court to believe that the Byzantine Second Council of Nicaea had approved the worship of images, which in fact was not the case. The Catholic counterblast set up out a centre course betwixt the extreme positions of Byzantine iconoclasm and the iconodules, approving the veneration of images for what they represented, but not accepting what became the Orthodox position, that images partook in some degree of the nature of the matter they represented (a belief later to resurface in the West in Renaissance Neo-Platonism).

To the Western church images were only objects made by craftsmen, to be utilized for stimulating the senses of the faithful, and to be respected for the sake of the subject represented, not in themselves. Although in pop devotional practise a tendency to become beyond these limits has often been nowadays, the church was, earlier the advent of the idea of collecting old art, usually brutal in disposing of images no longer needed, much to the regret of fine art historians. Most monumental sculpture of the first millennium that has survived was broken up and reused as rubble in the re-building of churches.

In practical matters relating to the use of images, as opposed to their theoretical place in theology, the Libri Carolini were at the anti-iconic end of the spectrum of Catholic views, being for instance rather disapproving of the lighting of candles earlier images. Such views were ofttimes expressed past private church building leaders, such as the famous example of Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, although many others leant the other way, and encouraged and commissioned art for their churches. Bernard was in fact only opposed to decorative imagery in monasteries that was not specifically religious, and popular preachers like Saint Bernardino of Siena and Savonarola regularly targeted secular images owned past the laity.

Early Middle Ages [edit]

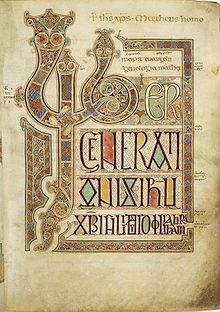

While the Western Roman Empire'due south political construction collapsed afterwards the fall of Rome, the Church building continued to fund art where it could. The virtually numerous surviving works of the early flow are illuminated manuscripts, at this date all presumably created by the clergy, frequently including abbots and other senior figures. The monastic hybrid between "barbarian" decorative styles and the book in the Insular art of the British Isles from the 7th century was to be enormously influential in European fine art for the rest of the Middle Ages, providing an alternative path to classicism, transmitted to the continent by the Hiberno-Scottish mission. At this flow the Gospel book, with figurative fine art confined more often than not to Evangelist portraits, was usually the blazon of book most lavishly decorated; the Book of Kells is the most famous instance.

The 9th century Emperor Charlemagne set out to create works of art appropriate to the status of his revived Empire. Carolingian and Ottonian art was largely confined to the circumvolve of the Imperial courtroom and different monastic centres, each of which had its own singled-out artistic style. Carolingian artists consciously tried to emulate such examples of Byzantine and Late Antique art as were bachelor to them, copying manuscripts similar the Chronography of 354 and producing works like the Utrecht Psalter, which however divides art historians as to whether it is a copy of a much earlier manuscript, or an original Carolingian creation. This in plow was copied three times in England, lastly in an Early Gothic way.

Ivory carvings, often for book covers, drew on the diptychs of Belatedly Artifact. For example, the front and back covers of the Lorsch Gospels are of a 6th-century Majestic triumph, adjusted to the triumph of Christ and the Virgin. Withal, they besides drew on the Insular tradition, especially for decorative item, whilst greatly improving on that in terms of the depiction of the human being figure. Copies of the scriptures or liturgical books illustrated on vellum and adorned with precious metals were produced in abbeys and nunneries beyond Western Europe. A piece of work like the Stockholm Codex Aureus ("Gilt Book") might exist written in gilded leafage on royal vellum, in imitation of Roman and Byzantine Regal manuscripts.[5] Anglo-Saxon fine art was ofttimes freer, making more use of lively line drawings, and there were other distinct traditions, such as the group of boggling Mozarabic manuscripts from Spain, including the Saint-Sever Beatus, and those in Girona and the Morgan Library.

Charlemagne had a life-size crucifix with the figure of Christ in precious metal in his Palatine Chapel in Aachen, and many such objects, all at present vanished, are recorded in large Anglo-Saxon churches and elsewhere. The Golden Madonna of Essen and a few smaller reliquary figures are at present all that remain of this spectacular tradition, completely outside Byzantine norms. Like the Essen figure, these were presumably all made of thin sheets of aureate or silver supported by a wooden core.

Romanesque [edit]

Romanesque art, long preceded by the Pre-Romanesque, developed in Western Europe from approximately 1000 AD until the rise of the Gothic style. Church-building was characterized by an increment in height and overall size. Vaulted roofs were supported by thick rock walls, massive pillars and rounded arches. The dark interiors were illumined by frescoes of Jesus, Mary and the saints, ofttimes based on Byzantine models.

Carvings in stone adorned the exteriors and interiors, particularly the tympanum in a higher place the principal archway, which oft featured a Christ in Majesty or in Judgement, and the large wooden crucifix was a German innovation right at the starting time of the catamenia. The capitals of columns were also oftentimes elaborately carved with figurative scenes. The ensemble of large and well-preserved churches at Cologne, then the largest metropolis northward of the Alps, and Segovia in Spain, are among the all-time places today to capeesh the affect of the new larger churches on a city mural, but many individual buildings exist, from Durham, Ely and Tournai Cathedrals to large numbers of individual churches, especially in Southern France and Italia. In more prosperous areas, many Romanesque churches survive covered up by a Baroque makeover, much easier to do with these than a Gothic church.

Few of the large wall-paintings that originally covered most churches have survived in good condition. The Final Judgement was normally shown on the western wall, with a Christ in Majesty in the alcove semi-dome. Extensive narrative cycles of the Life of Christ were developed, and the Bible, with the Psalter, became the typical focus of illumination, with much utilise of historiated initials. Metalwork, including decoration in enamel, became very sophisticated, and many spectacular shrines made to hold relics take survived, of which the best known is the Shrine of the Iii Kings at Cologne Cathedral past Nicholas of Verdun and others (ca 1180–1225).

Gothic art [edit]

The Western (Royal) Portal at Chartres Cathedral (ca. 1145). These architectural statues are among the earliest Gothic sculptures and were a revolution in way and the model for a generation of sculptors.

Gothic fine art emerged in France in the mid-12th century. The Basilica at Saint-Denis built by Abbot Suger was the outset major edifice in the Gothic style. New monastic orders, peculiarly the Cistercians and the Carthusians, were important builders who developed distinctive styles which they disseminated across Europe. The Franciscan friars built functional city churches with huge open naves for preaching to large congregations. Nonetheless, regional variations remained important, even when, by the late 14th century, a coherent universal style known as International Gothic had evolved, which connected until the late 15th century, and beyond in many areas. The chief media of Gothic fine art were sculpture, panel painting, stained glass, fresco and the illuminated manuscript, though religious imagery was also expressed in metalwork, tapestries and embroidered vestments. The architectural innovations of the pointed arch and the flying buttress, allowed taller, lighter churches with large areas of glazed window. Gothic fine art made total use of this new environment, telling a narrative story through pictures, sculpture, stained glass and soaring architecture. Chartres cathedral is a prime case of this.

Gothic art was often typological in nature, reflecting a belief that the events of the Old Attestation pre-figured those of the New, and that that was indeed their master significance. Sometime and New Attestation scenes were shown next in works like the Speculum Humanae Salvationis, and the decoration of churches. The Gothic flow coincided with a great resurgence in Marian devotion, in which the visual arts played a major part. Images of the Virgin Mary adult from the Byzantine hieratic types, through the Coronation of the Virgin, to more human and intimate types, and cycles of the Life of the Virgin were very pop. Artists like Giotto, Fra Angelico and Pietro Lorenzetti in Italy, and Early on Netherlandish painting, brought realism and a more natural humanity to fine art. Western artists, and their patrons, became much more confident in innovative iconography, and much more originality is seen, although copied formulae were all the same used by most artists. The book of hours was developed, mainly for the lay user able to afford them – the earliest known case seems to have written for an unknown laywoman living in a pocket-sized village near Oxford in almost 1240 – and now royal and aristocratic examples became the type of manuscript nearly often lavishly decorated. Most religious art, including illuminated manuscripts, was now produced by lay artists, but the commissioning patron often specified in particular what the piece of work was to comprise.

Iconography was affected by changes in theology, with depictions of the Supposition of Mary gaining ground on the older Expiry of the Virgin, and in devotional practices such as the Devotio Moderna, which produced new treatments of Christ in andachtsbilder subjects such every bit the Human of Sorrows, Pensive Christ and Pietà, which emphasized his man suffering and vulnerability, in a parallel movement to that in depictions of the Virgin. Many such images were now small oil paintings intended for private meditation and devotion in the homes of the wealthy. Even in Last Judgements Christ was now usually shown exposing his chest to show the wounds of his Passion. Saints were shown more than oftentimes, and altarpieces showed saints relevant to the item church or donor in attendance on a Crucifixion or enthroned Virgin and Child, or occupying the cardinal infinite themselves (this ordinarily for works designed for side-chapels). Over the menses many ancient iconographical features that originated in New Testament apocrypha were gradually eliminated under clerical pressure, similar the midwives at the Nativity, though others were too well-established, and considered harmless.[6]

In Early Netherlandish painting, from the richest cities of Northern Europe, a new minute realism in oil painting was combined with subtle and complex theological allusions, expressed precisely through the highly detailed settings of religious scenes. The Mérode Altarpiece (1420s) of Robert Campin and the Washington Van Eyck Annunciation or Madonna of Chancellor Rolin (both 1430s, by Jan van Eyck) are examples.[7]

In the 15th century, the introduction of cheap prints, by and large in woodcut, made it possible even for peasants to take devotional images at home. These images, tiny at the bottom of the market place, oftentimes crudely coloured, were sold in thousands but are at present extremely rare, most having been pasted to walls. Souvenirs of pilgrimages to shrines, such equally clay or lead badges, medals and ampullae stamped with images were also popular and cheap. From the mid-century blockbooks, with both text and images cut as woodcut, seem to have been affordable by parish priests in the Low Countries, where they were near popular. By the end of the century, printed books with illustrations, still mostly on religious subjects, were rapidly becoming attainable to the prosperous middle class, as were engravings of fairly high-quality past printmakers like Israhel van Meckenem and Primary E. S.

For the wealthy, pocket-size console paintings, even polyptychs in oil painting, were becoming increasingly popular, often showing donor portraits alongside, though ofttimes much smaller than, the Virgin or saints depicted. These were usually displayed in the home.

Renaissance art [edit]

![]()

Renaissance fine art, heavily influenced by the "rebirth" (French: renaissance) of interest in the art and culture of classical artifact, initially connected the trends of the preceding period without cardinal changes, merely using classical clothing and architectural settings which were later all very appropriate for New Testament scenes. However a clear loss of religious intensity is apparent in many Early Renaissance religious paintings – the famous frescoes in the Tornabuoni Chapel by Domenico Ghirlandaio (1485–1490) seem more interested in the detailed depiction of scenes of bourgeois city life than their actual subjects, the Life of the Virgin and that of John the Baptist, and the Magi Chapel of Benozzo Gozzoli (1459–1461) is more than a celebration of Medici status than an Arrival of the Magi. Both these examples (which still used contemporary clothes) come from Florence, the middle of the Early on Renaissance, and the place where the charismatic Dominican preacher Savonarola launched his set on on the worldliness of the life and art of the citizens, culminating in his famous Bonfire of the Vanities in 1497; in fact other preachers had been holding similar events for decades, but on a smaller scale. Many Early Renaissance artists, such as Fra Angelico and Botticelli were extremely devout, and the latter was one of many who fell under the influence of Savonarola.

The brief High Renaissance (c. 1490–1520) of Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael transformed Catholic art more fundamentally, breaking with the onetime iconography that was thoroughly integrated with theological conventions for original compositions that reflected both creative imperatives, and the influence of Renaissance humanism. Both Michelangelo and Raphael worked almost exclusively for the Papacy for much of their careers, including the twelvemonth of 1517, when Martin Luther wrote his Xc-Five Theses. The connection between the events was non just chronological, every bit the indulgences that provoked Luther helped to finance the Papal creative program, as many historians have pointed out.

Almost fifteenth-century pictures from this period were religious pictures. This is self-evident, in ane sense, but "religious pictures" refers to more than just a certain range of subject thing; it means that the pictures existed to meet institutional ends. The Church building commissioned artwork for 3 main reasons: The first was indoctrination, clear images were able to relay meaning to an uneducated person. The second was ease of call back, depictions of saints and other religious figures let for a point of mental contact. The third is to incite awe in the eye of the viewer, John of Genoa believed that this was easier to practice with image than with words. Because these three tenets, information technology tin be causeless that golden was used to inspire awe in the mind and eye of the beholder, where later during the Protestant Reformation the ability to return aureate through the use of plain pigments displayed an artist's skill in a mode that the application of gilt leaf to a console does not[ix]

The Protestant Reformation was a holocaust of art in many parts of Europe. Although Lutheranism was prepared to alive with much existing Catholic art and then long every bit it did not get a focus of devotion, the more radical views of Calvin, Zwingli and others saw public religious images of any sort as idolatry, and fine art was systematically destroyed in areas where their followers held sway. This subversive process continued until the mid-17th century, as religious wars brought periods of iconoclast Protestant control over much of the continent. In England and Scotland destruction of religious fine art, most intense during the English Republic, was especially heavy. Some rock sculpture, illuminated manuscripts and stained drinking glass windows (expensive to replace) survived, simply of the thousands of high quality works of painted and forest-carved art produced in medieval Britain, virtually none remain.[10]

In Rome, the sack of 1527 by the Catholic Emperor Charles V and his largely Protestant mercenary troops was enormously destructive both of art and artists, many of whose biographical records end abruptly. Other artists managed to escape to different parts of Italy, often finding difficulty in picking up the thread of their careers. Italian artists, with the odd exception like Girolamo da Treviso, seem to have had little attraction to Protestantism. In Germany, however, the leading figures such as Albrecht Dürer and his pupils, Lucas Cranach the Elderberry, Albrecht Altdorfer and the Danube school, and Hans Holbein the Younger all followed the Reformers. The development of German religious painting had come to an abrupt halt past virtually 1540, although many prints and book illustrations, especially of Old Attestation subjects, connected to be produced.

Council of Trent [edit]

Italian painting after 1520, with the notable exception of the art of Venice, adult into Mannerism, a highly sophisticated style, striving for effect, that drew the concern of many churchman that it lacked appeal for the mass of the population. Church building pressure to restrain religious imagery afflicted art from the 1530s and resulted in the decrees of the final session of the Council of Trent in 1563 including short and rather inexplicit passages concerning religious images, which were to have keen impact on the evolution of Cosmic fine art. Previous Catholic Church councils had rarely felt the demand to pronounce on these matters, unlike Orthodox ones which have often ruled on specific types of images.

The decree confirmed the traditional doctrine that images only represented the person depicted, and that veneration to them was paid to the person themselves, non the prototype, and further instructed that:

...every superstition shall be removed ... all lasciviousness be avoided; in such wise that figures shall non be painted or adorned with a beauty heady to lust... there be zip seen that is hell-raising, or that is unbecomingly or confusedly arranged, nothing that is profane, naught indecorous, seeing that holiness becometh the house of God. And that these things may be the more faithfully observed, the holy Synod ordains, that no 1 be allowed to place, or cause to exist placed, any unusual paradigm, in any identify, or church, howsoever exempted, except that epitome have been approved of by the bishop ...[eleven]

10 years after the prescript Paolo Veronese was summoned by the Inquisition to explain why his Concluding Supper, a huge canvass for the refectory of a monastery, contained, in the words of the Inquisition: "buffoons, drunken Germans, dwarfs and other such scurrilities" as well every bit extravagant costumes and settings, in what is indeed a fantasy version of a Venetian patrician banquet.[12] Veronese was told that he must change his painting within a three-month menstruation – in fact he only changed the title to The Feast in the House of Levi, still an episode from the Gospels, only a less doctrinally central one, and no more was said.[13] Merely the number of such decorative treatments of religious subjects declined sharply, as did "unbecomingly or confusedly arranged" Mannerist pieces, equally a number of books, notably by the Flemish theologian Molanus (De Picturis et Imaginibus Sacris, pro vero earum usu contra abusus ("Treatise on Sacred Images"), 1570), Cardinal Federico Borromeo (De Pictura Sacra) and Fundamental Gabriele Paleotti (Discorso, 1582), and instructions by local bishops, amplified the decrees, often going into minute particular on what was acceptable. 1 of the primeval of these, Degli Errori dei Pittori (1564), past the Dominican theologian Andrea Gilio da Fabriano, joined the chorus of criticism of Michelangelo's Concluding Sentence and defended the devout and simple nature of much medieval imagery. But other writers were less sympathetic to medieval fine art and many traditional iconographies considered without adequate scriptural foundation were in result prohibited (for example the Swoon of the Virgin), as was any inclusion of classical pagan elements in religious art, and almost all nudity, including that of the infant Jesus.[14] According to the medievalist Émile Mâle, this was "the death of medieval art".[xv]

Baroque art [edit]

Baroque art, developing over the decades following the Council of Trent, though the extent to which this was an influence on it is a matter of contend, certainly met virtually of the council's requirements, especially in the before, simpler phases associated with the Carracci and Caravaggio, who withal met with clerical opposition over the realism of his sacred figures.

Subjects were shown in a direct and dramatic mode, with relatively few abstruse allusions. Choice of subjects was widened considerably, equally Bizarre artists delighted in finding new biblical episodes and dramatic moments from the lives of saints. Equally the movement continued into the 17th century simplicity and realism tended to reduce, more slowly in Spain and France, only the drama remained, produced by the depiction of farthermost moments, dramatic movement, colour and chiaroscuro lighting, and if necessary hosts of agitated cherubs and swirling clouds, all intended to overwhelm the worshipper. Compages and sculpture aimed for the aforementioned effects; Bernini (1598–1680) epitomises the Baroque style in those arts. Bizarre fine art spread across Catholic Europe and into the overseas missions of Asia and the Americas, promoted by the Jesuits and Franciscans, highlighting painting and/or sculpture from Quito School, Cuzco School and Chilote Schoolhouse of Religious Imagery.

New iconic subjects popularized in the Bizarre period included the Sacred Heart of Jesus, and the Immaculate Conception of Mary; the definitive iconography for the latter seems to accept been established by the master and then begetter-in-law of Diego Velázquez, the painter and theorist Francisco Pacheco, to whom the Inquisition in Seville also contracted the approval of new images. The Assumption of Mary became a very mutual subject, and (despite a Caravaggio of the bailiwick) the Decease of the Virgin became almost extinct in Catholic fine art; Molanus and others had written confronting it.

18th century [edit]

In the 18th Century, secular Bizarre adult into the still more flamboyant but lighter Rococo style, which was hard to accommodate to religious themes, although Gianbattista Tiepolo was able to do so. In the later part of the century there was a reaction, especially in architecture, against the Baroque, and a turning back to more austere classical and Palladian forms.

Past now the charge per unit of production of religious art was noticeably slowing downward. After a spate of building and re-building in the Bizarre period, Cosmic countries were generally clearly overstocked with churches, monasteries and convents, in the case of some places such equally Naples, almost absurdly so. The Church was now less important as a patron than royalty and the aristocracy, and the eye class need for fine art, mostly secular, was increasing rapidly. Artists could now have a successful career painting portraits, landscapes, still lifes or other genre specialisms, without e'er painting a religious field of study – something unusual hitherto unusual in the Catholic countries, though long the norm in Protestant ones. The number of sales of paintings, metalwork and other church fittings to private collectors increased during the century, especially in Italy, where the G Tour gave ascension to networks of dealers and agents. Leonardo da Vinci's London Virgin of the Rocks was sold to the Scottish artist and dealer Gavin Hamilton by the church building in Milan that information technology was painted for in about 1781; the version in the Louvre having apparently been diverted from the same church 3 centuries earlier by Leonardo himself, to become to the Male monarch of France.

The wars following the French Revolution saw big quantities of the finest art, paintings in item, carefully selected for appropriation past the French armies or the secular regimes they established. Many were sent to Paris for the Louvre (some to somewhen be returned, others not) or local museums established by the French, like the Brera in Milan. Suppression of monasteries, which had been under way for decades under Catholic Enlightened despots of the Ancien Régime, for example in the Edict on Idle Institutions (1780) of Joseph Two of Austria, intensified considerably. By 1830 much of the best Catholic religious art was on public brandish in museums, as has been the case ever since. This undoubtedly widened access to many works, and promoted public sensation of the heritage of Cosmic art, but at a cost, as objects came to be regarded every bit of primarily artistic rather than religious significance, and were seen out of their original context and the setting they were designed for.

19th and 20th centuries [edit]

The 19th Century saw a widespread repudiation by both Catholic and Protestant churches of Classicism, which was associated with the French Revolution and Enlightenment secularism. This led to the Gothic Revival, a render to Gothic-influenced forms in architecture, sculpture and painting, led by people such as Augustus Pugin in England and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc in France. Across the world, thousands of Gothic churches and Cathedrals were produced in a new moving ridge of church-building, and the collegiate Gothic fashion became the norm for other church building institutions. Medieval Gothic churches, peculiarly in England and France, were restored, often very heavy-handedly. In painting, like attitudes led to the High german Nazarene movement and the English language Pre-Raphaelites. Both movements embraced both Catholic and Protestant members, but included some artists who converted to Catholicism.

Exterior these and like movements, the establishment fine art world produced much less religious painting than at whatever fourth dimension since the Roman Empire, though many types of applied art for church fittings in the Gothic style were made. Commercial pop Cosmic art flourished using cheaper techniques for mass-reproduction. Colour lithography made it possible to reproduce coloured images cheaply, leading to a much broader circulation of holy cards. Much of this art connected to use watered-down versions of Baroque styles. The Immaculate Heart of Mary was a new subject of the 19th century, and new apparitions at Lourdes and Fátima, besides as new saints, provided new subjects for art.

Architects began to revive other earlier Christian styles, and experiment with new ones, producing results such every bit Sacre Coeur in Paris, Sagrada Familia in Barcelona and the Byzantine-influenced Westminster Cathedral in London. The 20th century led to the adoption of modernist styles of architecture and fine art. This motion rejected traditional forms in favour of utilitarian shapes with a bare minimum of decoration. Such art as in that location was eschewed naturalism and homo qualities, favouring stylised and abstract forms. Examples of modernism include the Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King, and Los Angeles Cathedral.

Modern Cosmic artists include Brian Whelan, Efren Ordonez, Ade Bethune, Imogen Stuart, and Georges Rouault.[sixteen]

21st century [edit]

The early adoption of modernist styles at the dawn of the 21st century connected with the trends from the 20th century. Artists began to experiment with materials and colours. In many cases this contributed to simplifications which led to resemblance to the early Christian art. Simplicity was seen as the best mode to bring pure Christian messages to the viewer.

Subjects [edit]

The Ghent Altarpiece: The Admiration of the Lamb (interior view) painted 1432 past Jan van Eyck

Some of the most mutual subjects depicted in Cosmic fine art:

- Category:Christian iconography

Life of Christ in art:

- Annunciation

- Nascency of Jesus in art

- Adoration of the Magi

- Adoration of the shepherds

- Baptism of Jesus

- The Last Supper

- Abort of Jesus

- The Raising of the Cross

- The Crucifixion

- Descent from the Cross

- Noli me tangere

- Ascension of Jesus

- Christ in Majesty

Mary:

- Roman Cosmic Marian art

- Life of the Virgin

- Christ taking leave of his Mother

- Death of the Virgin

- Supposition of the Virgin Mary in art

- Coronation of the Virgin

- The Holy family unit

- Madonna (art)

- Madonna and Child

- Hortus conclusus

- Holy Kinship

Other:

- The Trinity in Art

- Angels in art

- Evangelist portrait

- Maestà

- Stations of the Cross

- Tree of Jesse

See likewise [edit]

- Christian art

- Catholic culture

- Roman Catholic Marian art

- Early Renaissance painting

- Bizarre compages

- Listing of illuminated manuscripts

- Western Painting

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ "The figure (...) is an apologue of Christ as the shepherd" Andre Grabard, "Christian iconography, a study of its origins", ISBN 0-691-01830-8

- ^ Jean Lassus. Landmarks of Western Art. Ed. B Myers, T Copplestone. (Hamlyn Publishing, 1965, 1985) p.187.

- ^ Westward.F. Volbach, Elfenbeinarbeiten der Spätantike und des frühen Mittelalters (Mainz, 1976).

- ^ T. Mathews, The early churches of Constantinople: architecture and liturgy (University Park, 1971); N. Henck, "Constantius ho Philoktistes?", Dumbarton Oaks Papers 55 (2001), 279-304 (available online Archived 2009-03-27 at the Wayback Auto).

- ^ Michelle P. Brown. How Christianity came to Britain and Ireland. (King of beasts Hudson, 2006) pp. 176, 177, 191

- ^ Male, Emile (1913) The Gothic Image, Religious Art in France of the Thirteenth Century, p 165-viii, English trans of tertiary edn, 1913, Collins, London (and many other editions) is a archetype work on French Gothic church art

- ^ Lane, Barbara G,The Chantry and the Altarpiece, Sacramental Themes in Early on Netherlandish Painting, Harper & Row, 1984, ISBN 0-06-430133-viii analyses all these works in detail. Come across also the references in the articles on the works.

- ^ The birth and growth of Utrecht Archived 2013-12-fourteen at the Wayback Automobile

- ^ Alberti, Leon Battista. On Painting. Princeton University Press, 1981, p. 215.

- ^ Roy Potent. Lost Treasures of Britain. (Viking Penguin, 1990) pp.47-65.

- ^ "CT25". history.hanover.edu . Retrieved 2020-12-01 .

- ^ "Transcript of Veronese's testimony". Archived from the original on 2009-09-29. Retrieved 2008-06-28 .

- ^ David Rostand, Painting in Sixteenth-Century Venice: Titian, Veronese, Tintoretto, 2d ed 1997, Cambridge UP ISBN 0-521-56568-5

- ^ Blunt Anthony, Artistic Theory in Italy, 1450–1660, chapter VIII, especially pp. 107-128, 1940 (refs to 1985 edn), OUP, ISBN 0-19-881050-4

- ^ The death of Medieval Fine art Extract from book by Émile Mâle

- ^ "Georges Rouault, French Expressionist Painter". www.visual-arts-cork.com . Retrieved 2020-12-01 .

References [edit]

- Levey, Michael (1961). From Giotto to Cézanne. Thames and Hudson. ISBN0-500-20024-half dozen.

- Beckwith, John (1969). early Medieval Art. Thames and Hudson. ISBN0-500-20019-10.

- Rice, David Talbot (1997). Art of the Byzantine Era. Thames and Hudson. ISBN0-500-20004-1.

- Myers, Bernard; Trewin Copplestone Ed. (1985) [1965]. Landmarks of Western Art. Hamlyn. ISBN0-600-35840-2.

- Brown, Michelle P. (2006). How Christianity Came to Uk and Ireland. Lion Hudson. ISBN0-7459-5153-eight.

- Strong, Roy (1990). Lost Treasures of Britain. Viking Penguin. ISBN0-670-83383-5.

- Jean Soldini, "Storia, memoria, arte sacra tra passato east futuro", Sacre Arti , F. Gualdoni ed. et Tristan Tzara, Due south. Yanagi, Titus Burckhardt, Bologna, FMR, 2008, p. 166–233. ISBN 9788887915402.

External links [edit]

- Christian Iconography from Augusta State University.

- "The Function of Fine art". Archived from the original on 29 August 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-08 .

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Age of spirituality : tardily antiquarian and early Christian art, tertiary to seventh century from The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catholic_art

0 Response to "What Era Was Religious Art and Statuary Destroyed in History"

Post a Comment